Preface by Eileen: A few weeks ago I contacted my first cousin, Dennis, oldest son of my Uncle Bill, because a line he had written for a family project assembled in 1998 was coming into my mind. Of all that he wrote, that line has sometimes come back easily into my memory. The sentences (woven into a more recent, more extensive piece Dennis did for a wonderful collection of family history, genealogy and old photos) appear later in his writing below and are: “Two generations ago most people were still connected to the land—there was a home place that held people together. The family farm or homestead, even if it was just a few acres like Luther and Orpha’s, made it possible for people to survive a Great Depression. It therefore seems appropriate that I focus on the place where these two people lived out their lives, for environment shapes and sustains us in so many ways.”

It has been good to connect with Dennis again both as family and as a fellow writer, and I am pleased to have this piece as my first hosted Guest Writing. I hope you will enjoy the richness of experiences and insights penned by him.

LOSING THE LAND

My father’s father, Luther, fed eight kids

from a couple acres at Locust Grove.

They lived in a tiny old house full of big memories.

I never knew it was an ancient log cabin until

I got the photograph in the mail

of it being torn down

after the auction.

My mother’s father, Amos, farmed hundreds of acres

where Little Antietam Creek flows out of Baker’s Hollow.

Apple orchards, hay fields, dairy cows.

It’s carved up now,

like a Thanksgiving turkey on the realtors’ plates.

It started when I left home,

new power lines humming in the damp fog,

menacing steel towers marching across the fields.

Then came the survey stakes,

the percolation tests,

the well drillers,

spelling the end.

— Dennis Slifer, 1998

Memories of My Grandparents

by Dennis Slifer

How far back should I look in describing where I come from and who I think I am? Grandparents? Great-grandparents? Neolithic tribesmen in ancient Europe? Maybe I’m descended from Otzi—the name given to the 5,000-year-old, bronze-age man whose body was discovered preserved in glacial ice in the Alps a few years ago. We are all descended from something similar. It is not until after the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century that our ancestors differentiate much in terms of their lot in life.

I come from a long line of yeoman farmers—husbands of the land. Webster defines yeoman as a small farmer who cultivates his own land or one who performs great and laborious services; and husband as a frugal manager. Although I have had dirt under my fingernails and calluses on my hands, for the most part my life is very different from my forebears.

My grandparents undoubtedly had harder lives physically but they must have been more hopeful about life and the future, despite the trauma of two world wars and the Great Depression of the 1930’s. At least the natural world was still relatively intact for them, and the social fabric had not yet begun to unravel.

I cannot separate who I am from land and place. I am aware of my connection with that fertile ground that nourished my early years in the Valley and Ridge Province of the Appalachian Mountains. It is the watershed of the Potomac River and Little Antietam Creek in western Maryland—a pretty, pastoral landscape appropriately known as Pleasant Valley, at the foot of South Mountain. It is a land of many streams and fertile limestone soil that supported great hardwood forests, abundant wildlife and productive farms.

The farms I grew up with are mostly gone now—turned into housing tracts and trophy homes. We have lost the land, not only from my family but also from the landscape at large. It is fast becoming a homogenous suburbia from whence people commute to big cities. I don’t think my grandparents realized what was coming, just over the horizon. They were lucky, I think, to have exited before the heartbreaking loss became evident. But my parents saw it creeping in every day, all around them, and I cringe to see the changes when I return home. My grandchildren will not know what has been lost, having no baseline with which to compare the world they see. This is why I share with them these words and pictures of what I witnessed during my life—the spoiling of an exquisite landscape and the disappearance of an authentic way of life of its early residents.

To tell the family tree here is to acknowledge its fragmentary nature. Most of my ancestors are doomed to obscurity. My knowledge of the known ones consists mainly of just their names, dates of birth and death, and lists of their children—typically six to fifteen (is it a wonder the world is so crowded?). But from our oral family history and courthouse records it is possible to glean tantalizing bits of information about a few who seem like colorful characters—ancestors I wish I knew more about.

I have mentioned Jesse Reeder, my great-great-great-great grandfather who bought land near Park Hall, Maryland in 1795. We know he was in a militia group in the American Revolution, so there is at least one revolutionary character in the gene pool—perhaps even a romantic idealist! Moreover, he seems to be linked to one John Reeder who first appears in St. Mary’s County, Maryland in 1634—the year the State of Maryland was founded by Lord Calvert.

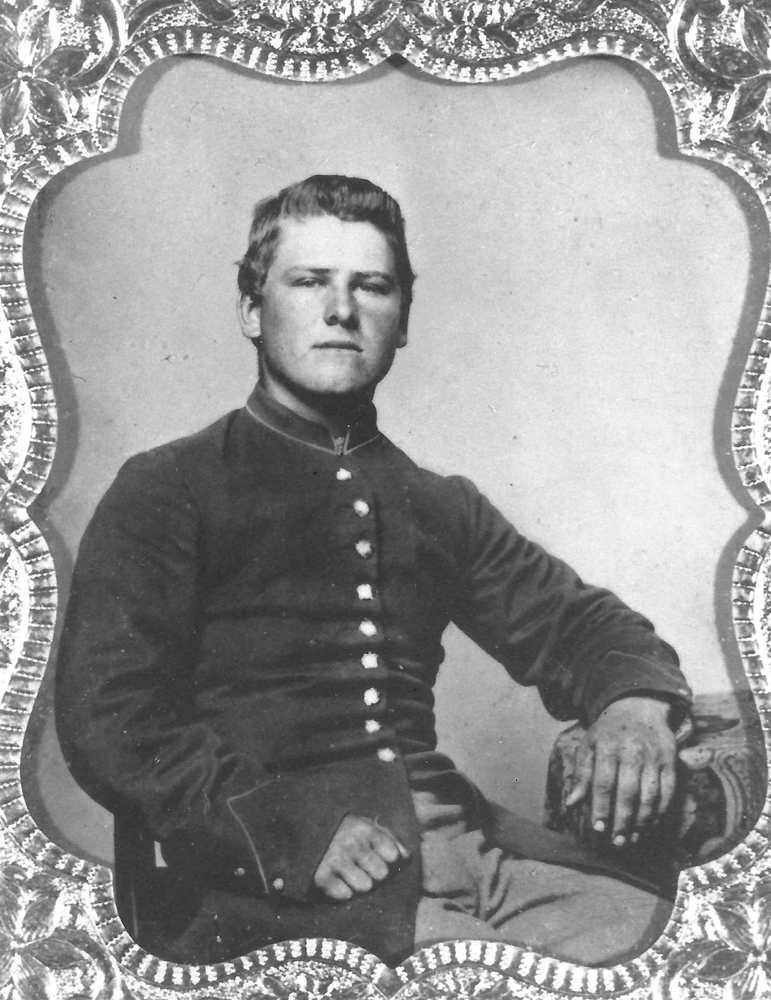

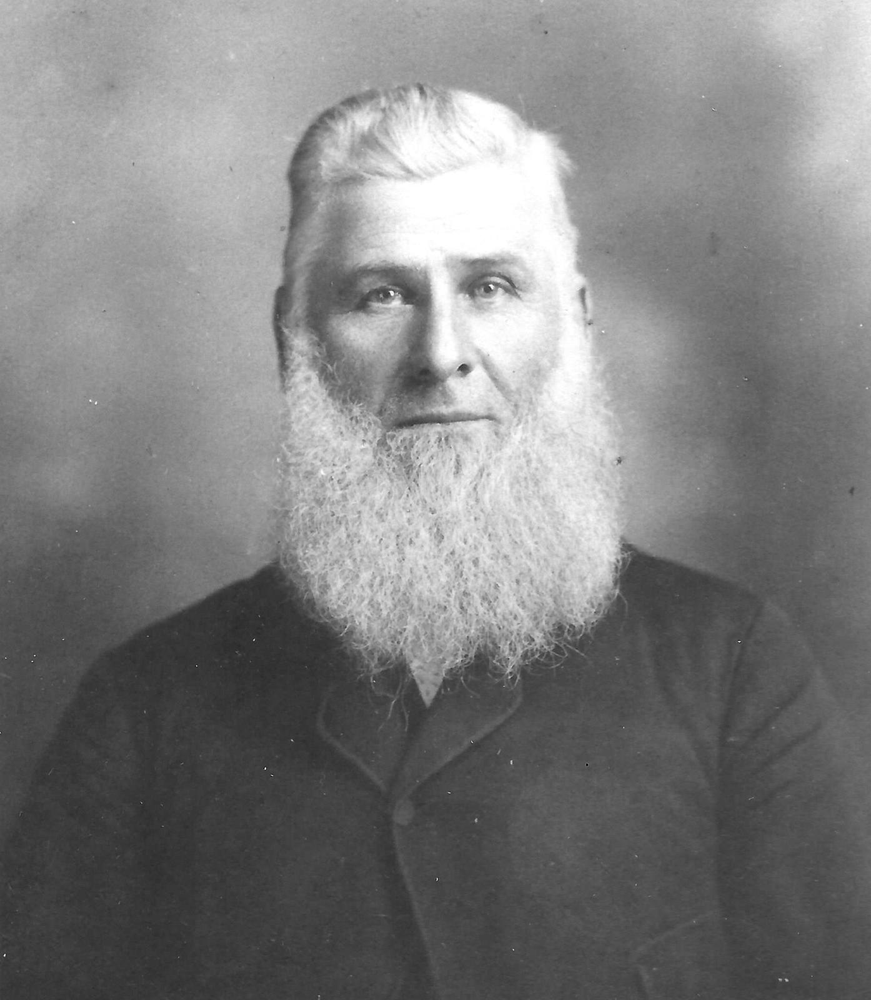

Another Reeder of note among my lineage is Andrew Jackson Reeder, born in 1839. Among his nine children was Andrew Grant Reeder, my great-grandfather. Andrew Jackson Reeder had red hair and beard, and was called Red. He allegedly had a penchant for heavy drinking and rowdiness. During the Civil War, Red served as a private in the Union Army, Third Regiment of the Potomac Home Brigade. This unit confronted the invading Confederates’ advance into Maryland in July, 1864, and had a “lively and gallant skirmish with the enemy to the west of Frederick.” My grandfather Reeder’s farm, the place I grew up, is about 30 miles west of Frederick and near the site where General Reno was killed in a cavalry skirmish. I have a Union belt buckle my Grandfather found in the soil there. Later this unit was ordered to “give battle to overwhelming force of enemy, in order to enable reinforcements to reach and protect the Capitol at Washington.”

Ironically, my other great-grandfather, Joshua Slifer, also served in this same outfit but it is unknown if he and Red were acquainted. Red is said to have gone AWOL during the war (perhaps he found some good whiskey), and for punishment was made to float down the Potomac River ensconced in a barrel. It would have been appropriate punishment if this was a whiskey barrel, and perhaps that was the idea—like tying a dead chicken to a dog that killed chickens. Did it make Red stop drinking, or make him even more rowdy? We’ll never know because nothing was written. After the Civil War he received a veteran’s pension of $12 a month, and settled down to become a farmer. At least we assume he settled down. Maybe he kept a hidden whiskey still in the forest of Baker’s Hollow where I roamed as a boy.

The Slifer genealogy is traced to our first known ancestor in this country, Johannes Schleipher, who was born in Orberschweil Parish, Switzerland in 1718. He left there for America and arrived on the ship Lydia in Philadelphia on December 11, 1739. He showed his allegiance to this country by signing his name in German script at the courthouse in Philadelphia. He was 21 years old when he landed in North America. His son John may have served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Wouldn’t it be great to have a record of their impressions then? We’ll never know.

My experience with ancestors starts with grandparents. I was lucky to be the first-born and have several decades to know all four of my grandparents before they died. Until I left home at eighteen, I lived within bicycle range of them. I ate meals at their tables, slept in their houses, and worked in their fields. I wish I had better appreciated this rare and fleeting time; it is with the clarity of hindsight that I value it. In rural Washington County, Maryland in the 1940s and 1950s, life revolved around family, church, and gardening. We frequently visited our relatives—grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—for they all lived close by.

Amos and Margie Reeder

For the first five years of my life, I lived in the same house with my mother’s parents, Amos Reeder (1893-1961) and Margie Baker Reeder (1893-1984). They had spent most of their lives on the Reeder family farm south of Boonsboro, but had bought a big Victorian house on the Main Street of town a few years before I was born. It was big enough to divide in two, so after I was born my parents moved into the other half. I was Amos and Margie’s first grandchild, so must have received a lot of attention. I have fond memories of that old house, and it is always associated with feelings of being loved. That house has been in my dreams more than any other place, so it must represent something archetypal and fundamental to my identity. Sadly, like the land and farms, that nurturing old symbol of a home has also been sold out of the family.

Amos and Margie were well known, respected members of the community. He was elected a county commissioner in 1950. They had been successful farmers due to a lifetime of hard work; the county road that runs by their farm—where I lived for six years and my parents lived out their lives—is named Amos Reeder Road in testimony to his standing in the community.

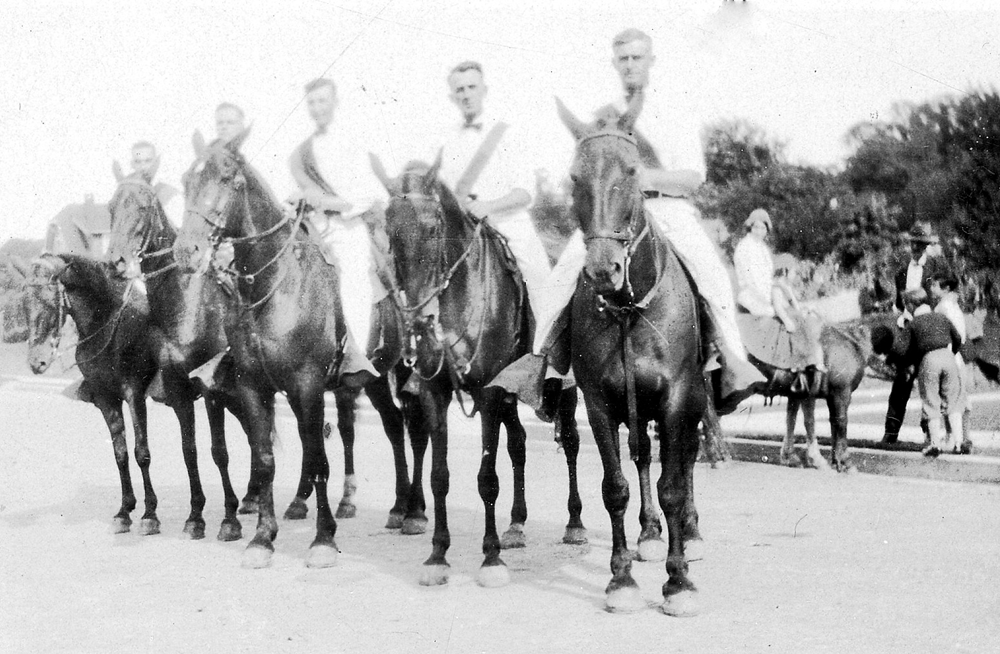

Amos drove classic Buick Roadmasters but I also like to think of him as the proud young man siting confidently on a strong black horse in one of the earliest photographs I have of him. In reminiscing on their courtship, my grandmother told me Amos always had the nicest horses around. He courted her on horse-back and they took winter sleigh rides in the snow. Of course I only knew Amos and Margie as “old” people—Ma Maw and Pap—from my perspective as a child, but also as a result of forty-plus years working on the farm. One of my favorite old photographs shows them in their work clothes at the farm sometime in the 1940s. They look tired and weather-beaten, as if they had just come in from a long, hot day working in the fields or a hot kitchen. Amos is visibly darkened from working long days in the sun. I love that picture because it is so real. It seems to tell more about their lives and character than other, more formal photographs.

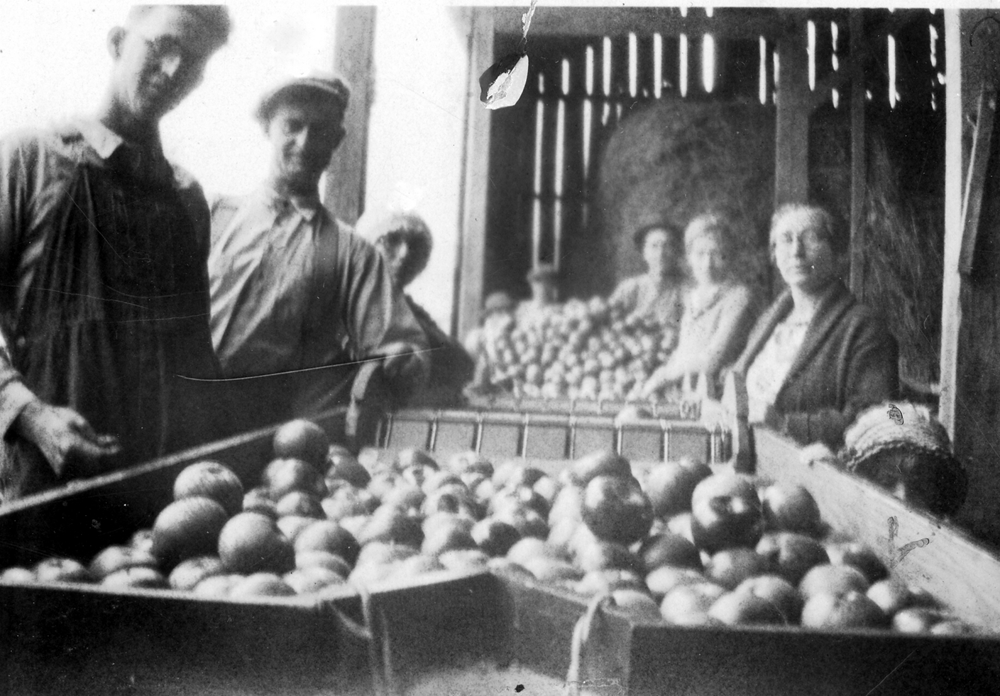

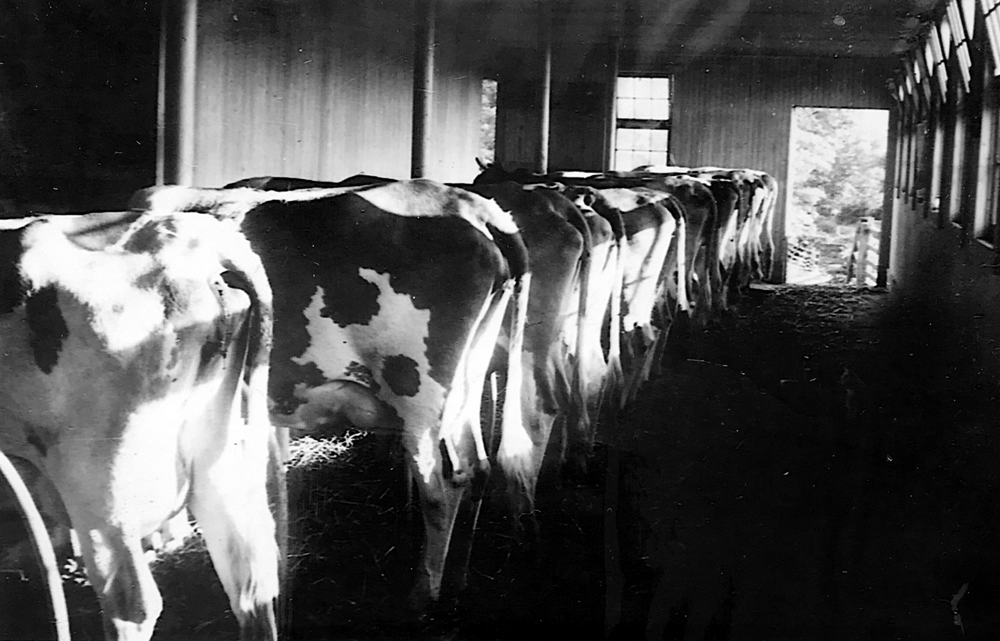

Amos and Margie succeeded, even through the Great Depression of the 1930s, because they were smart, frugal, and hard working. The records Amos kept of his finances on the farm are quaint and reveal much about the man and the times (with notes such as the price he got for eggs or hogs, the cost of fencing and medicine for the animals, the vagaries of weather, how many days neighbors worked for him at harvest time). He started out with the original Reeder farm (was this Jesse’s “Reeder’s Delight”?), where he was born in 1893 in a small log cabin built by his father on the east slope of South Mountain. The cabin still stands but it has been moved twenty miles to serve as an exhibit in the Washington County Agricultural Heritage Museum. Amos later bought the adjoining 150-acre farm north of Little Antietam Creek, and combined them into one operation. Under his stewardship the land flourished, and in making the transition from farming with horses and mules to tractors and trucks, Amos ran a dairy and a fruit orchard in addition to the other standard agriculture of the time. Amos and Margie’s farm provided jobs for a number of local people, who helped with milking cows, picking apples, making hay, and other chores. They raised two children—Virginia (my mother) and James—who lived most of their lives on the edge of the farm. Now it has been subdivided and sold out of the family.

The farm in its prime must have been a wonderful sight. In addition to the herd of dairy cows and the bountiful apple orchards, there were the usual chickens and turkeys, pigs, gardens, and fields of corn, hay, and other crops. I remember the farm auction when they sold all the livestock and equipment. It seemed exciting and exotic to my young eyes, too young to sense the sad finality of such events—the end of farming. I used to play in the cavernous old barn—in the haylofts and the dark, musty animal stalls beneath. I recall the old apple-packing shed where baskets and ladders hinted at the busy activities that used to occur there. My parents met during the fall apple harvest. My dad, a teenager then, was one of the workers Amos hired to help with the harvest. He drove the ancient flatbed truck through the orchard, collecting the apple crates. Amos was renowned for his apples—the finest were shipped as far off as England. I remember the old tool shed, filled with all sorts of paraphernalia and smelling of oil and kerosene. I liked to “ride” the old whetstone, sitting in the steel tractor seat and peddling the contraption to make the big stone wheel spin. Grooves were worn in its surface from years of use sharpening blades of all kinds. I remember Amos picking out a few of his favorite tools to keep from that old shed before the auction took place. I still have some—a huge iron padlock and key, a handsome and well-used pocketknife that he carried in the fields, and tree pruning shears.

I also have a gold watch with “Amos Reeder Ten-Ton Tomato Club” inscribed on its back. Awarded to Amos by an agricultural association, it commemorates his prodigious production. He grew fields of tomatoes and hauled them to a commercial cannery. I worked picking tomatoes as a summer job for my Uncle James after Amos and Margie retired and moved to town. It was some of the hardest and hottest work I ever did; it taught me the value (and cost) of things like farm labor. The enjoyable part of that job (other than tossing the occasional rotten tomato at fellow pickers) was getting to ride in the cantankerous old flat-bed truck with the loads of tomatoes that we delivered to the cannery at the “penal farm” (a state penitentiary) near Keedysville. The armed guards and sullen prisoners who unloaded the truck made these trips seem adventurous. The guards always looked under the truck when we drove out of the place to make sure no prisoners were clinging beneath it to escape. In case they had missed one, I sometimes looked under the chassis to reassure myself when we got back to the farm.

As a boy, I helped with making hay on the farm—probably some of the last crops taken from its fields. It was hot, sweaty, dusty, itchy work—as all old-time hay making was before the advent of machinery that makes huge bales that don’t require handling. But it was fun riding on the wagon behind the bailer, catching and stacking the bales as they popped out of the chute from the bailer. The fragrance of a newly mowed hay field is delightful, as is the sight of a barn filled to the roof with new hay. Years later I would relive some of these sensations and memories by cutting hay on land I bought in Virginia. Something of the essence of my childhood is always stirred by the scent of newly mowed hay and the sweet honeysuckle blooms that covered fences along the rural roads on which I rode my bike.

I was staying with Amos and Margie the night Amos had his fatal heart attack. I was 14, and remember the look of pain and fear on his face as he was carried out of the house gasping for air, and taken to the Veterans Administration Hospital where he died that night. He had been in the Army during WW I, but had been spared being sent overseas because he nearly died with the great influenza epidemic (the Spanish flu) that swept the country from 1918 to 1920. After his death I stayed with my grandmother often. Mamaw cooked my favorite dishes for me when I was there, typically fried chicken or fried chicken livers along with green beans cooked with ham, and I did yard work for her—mow grass, spade the garden, prune trees and shrubs. It was not nearly enough to repay her kindness and sacrifice.

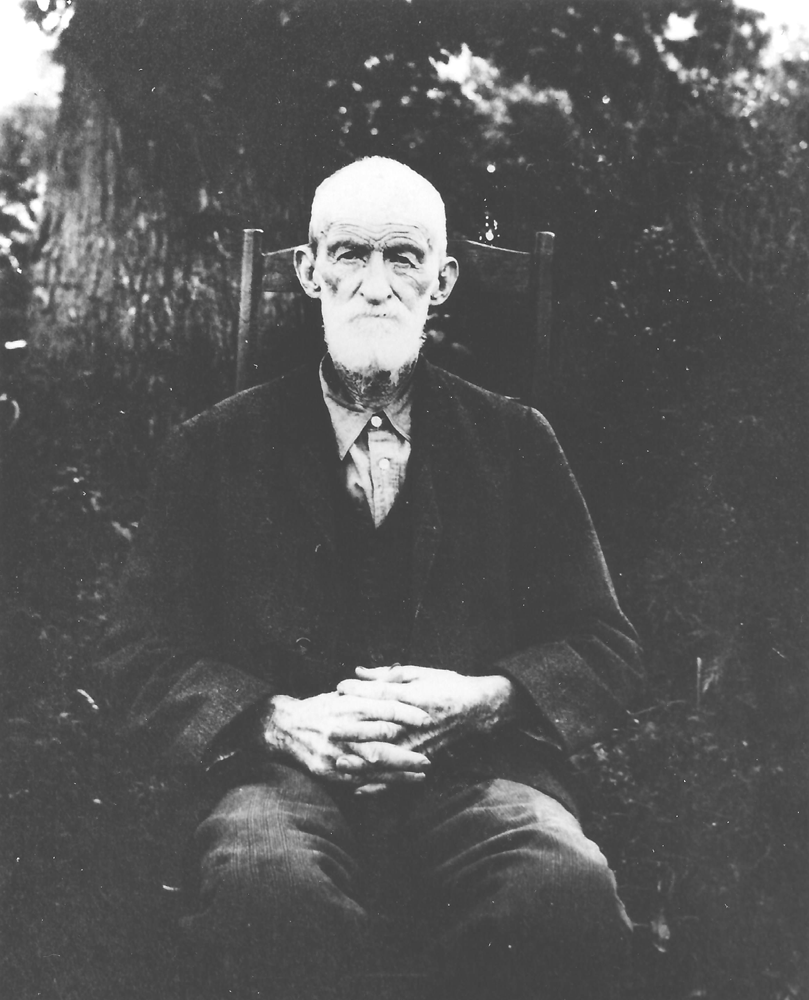

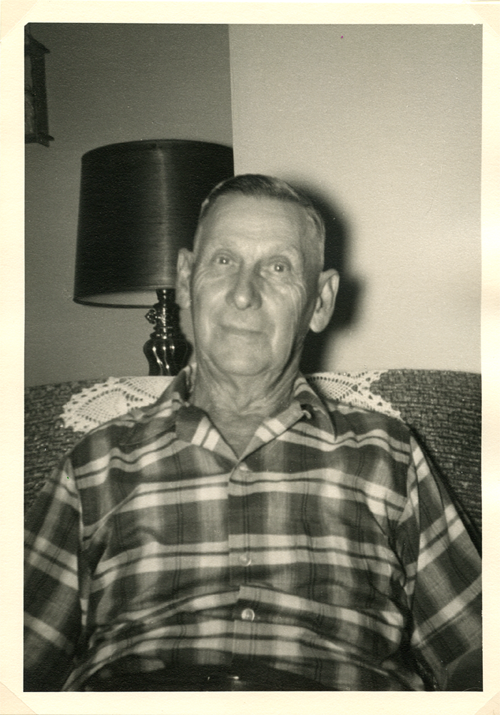

Luther and Orpha Slifer

I am equally proud to chronicle the lives of my paternal grandparents, Luther Slifer (1891-1972) and Orpha Grimm Slifer (1893-1985). Their names seem quaint, archaic, medieval-sounding, like characters in an opera or folk tale. I admire the way they lived and am grateful I had the chance to know them. I took them for granted too, along with their wisdom and experiences—not realizing how short the time would be to learn from them or that what they had to teach me was of value. It may sound clichéd, but it bears repeating that my grandparents came of age in another century—before electricity, telephones, television, airplanes, internet and computers, or automobiles. In fact, Luther and Orpha never owned a car and never had driver’s licenses. Two generations ago most people were still connected to the land—there was a home place that held people together. The family farm or homestead, even if it was just a few acres like Luther and Orpha’s, made it possible for people to survive a Great Depression. It therefore seems appropriate that I focus on the place where these two people lived out their lives, for environment shapes and sustains us in so many ways.

The old Slifer Place, unfortunately, no longer exists. I can hardly recognize the location now. The people who bought it at auction demolished the old house to make way for a new, modern house. The quaint old outbuildings are gone too—no more chicken house, pig pen, outhouse, summer kitchen and root cellar. The property was sold at auction in 1972 after Luther died. Nobody in the Slifer clan wanted it badly enough to try to keep it in the family, and I lacked resources and awareness at the time. This scene is played out across America thousands of times every year, as the children and grandchildren are scattered by their careers to subdivisions and apartments—farther from the land.

I never realized the old house was made of hewed logs until my parents sent me a photograph of its ancient skeleton stripped bare and exposed to the elements after providing shelter to generations of Slifers. It was very sad to look at that photograph, knowing that not only were Luther and Orpha and their eight kids gone, but also now their home itself was about to disappear. I wished I could have rescued that old house—salvaged the old hewed logs and reassembled them on my land in Virginia. But it was too late, an impossible dream, especially from 2,000 miles away in New Mexico where I lived at the time. Although it is usually impractical, I think old ancestral houses that have seen so much living should not be torn down. I would like to be able to visit the places of all my ancestors—even back to the painted caves of Stone Age Europe if it were possible. In the desert Southwest the Pueblo Indians trace their ancestors back to a sacred place of origin called the sipapu (“earth-navel,” literally a hole in the ground inside their kivas). We Slifers, Reeders, Grimms, Bakers, etc. seem to be losing reference to our earth-navels, along with approximately 300 million other Americans. Several more generations of screen time, obsessed on our devices, should complete the process.

The old Slifer place had low ceilings, which is not unusual for log houses. Luther and Orpha were short enough that they could stand upright in it, but their sons and grandsons, who grew up to be six feet tall, had to stoop or twist their head to the side in order to stand in the kitchen, and had to duck under the even-lower doorways when entering or leaving the room. The kitchen smelled delicious when I was a kid, for Grandmother Slifer was often cooking hearty meals or baking cookies in the oven of the old wood-burning cook stove. Sometimes the surface of the kitchen table would be covered with racks of homemade cookies that were cooling before being put in big jars and stashed in the cave-like pantry (whose shelves were packed with jars of home-canned food). I was happy to visit at such times and consumed a great many cookies, especially around Christmas time.

Another memory is of hog-butchering time. I witnessed this at a young age and it may have been one of the last times they butchered their own hogs. It was a big production of course, and even at my tender age I could appreciate how much work it was. Things started happening very early in the morning before the sun was up. It was cold weather—late fall or early winter, probably around Thanksgiving time. The great vats of boiling water made lots of steam and the air was pungent with wood smoke. Many relatives and neighbors came to lend a hand with the work. The hogs were killed with a rifle shot to the head, and the scene was bloody afterward. Large wooden planks and tables were set up, on which to process the meat. I was fascinated with the sausage-making process of grinding up meat and stuffing it into intestines. There were big hams and slabs of bacon to salt and hang in the cellar for curing, and the day culminated in a marvelous feast.

There were always chickens around the homestead—the crowing of roosters, clucking of hens, and peeping of chicks was an integral part of daily life. I enjoyed going to the hen house with Grandpap to collect eggs or feed the chickens. The chicken yard had a big grape vine growing in it, and in the summer when Japanese Beetles were devouring the grape leaves, Grandpap would periodically shake the vines to knock the beetles off; the chickens rushed under the grape vine to gobble up the beetles that fell to the ground. What boy would not enjoy that spectacle? I thought it was very clever to grow grapes in the chicken yard. Potatoes also come to mind, lots and lots of potatoes, for they were the staff of life on the Slifer place. Having an adequate potato crop was critical. I can still feel the cool damp air of the cellar with whitewashed stonewalls where the potatoes were stored through the winter.

Luther and Orpha never had plumbing in their house. They got water from a cistern and an old hand-dug well in the yard. It was an old-fashioned well like the ones in fairy tale books, with a stone base and a wooden frame and crank that raised a bucket of water up from the depths. As a teenager, I learned from Grandpap about the Hog Maw caves nearby (Hog Maw is the name of a place a few miles away); I soon explored that wet underworld with a fascination that would shape my life. The buckets of well water would be carried into the kitchen. On the other side of the yard sat the outhouse. When I was a child it was rather ancient-looking with cracks between the boards through which the wind blew. I would go inside to hide and spy at the outside world through those cracks. When I was a teenager, my father built Luther and Orpha a new concrete-block outhouse (no cold winter winds blowing through that one!), and located closer to the house.

The gardens and crops were always a prime topic of conversation, and we usually went out to inspect them whenever we visited—often this was on Sunday after church in Rohrersville. Grandmother Slifer took pride in her flowers, and her rose bushes were especially nice. Fruit trees were well cared for and treasured; I especially remember peach trees and the succulent flavor of fresh peaches plucked from those tree. There was a large old English walnut tree in their yard, which I enjoyed climbing. Some years this old tree would be host to hundreds of cicadas (locusts), whose shells became the Martian army for my toy soldiers to combat.

Among grandpap’s special cash crops were strawberries and raspberries. He had a couple acres of raspberries but that was a lot of work for a man to keep up. When the berries were ripe in the summer he hired me and other pickers to help him. I rode my bicycle from home near Boonsboro, about five miles to his place. We started early in the morning while it was still cool. It was pleasant work for the first few hours and I ate a lot of those juicy berries. For lunch, Grandmother cooked a hearty meal for us. The afternoons could be hot, hard work but Grandpap kept a steady pace and set a good example of old-time work ethic. He taught me the good sense of wearing a straw hat in the sun.

Luther took pride in the quality of his berries and other crops, and deservedly so—I have never tasted better berries than those I gorged on in his berry patch! He was obviously a master at coaxing living things out of the soil on his few acres in Locust Grove, and the land responded to his care and good husbandry. This quiet, gentle, hard-working man supported a large family throughout the Great Depression with very little cash income, by the fruits of his labor on the land. This was not what most people would call a farm—only about four acres, with no barn, draft animals, or tractor. When he needed a horse for plowing, hauling firewood, or other work he traded his labor for the use of a neighbor’s or relative’s draft animal. He hunted rabbits and squirrels to put extra meat on the table, and his letters suggest there were times when he could only afford to buy a few shotgun shells at a time from Poffenberger’s, the old country store nearby. Luther and Orpha were probably about as self-reliant as people could be in those days. They were part of a community of friends and relatives who helped each other.

As a child I never thought of my grandparents as poor—they seemed to have enough—but reading Luther’s letters makes it obvious that hard times were not unknown. I was amazed to learn that, despite working so hard their entire lives, they were never able to pay off the principal on their mortgage—the interest payments were all that could be managed from odd jobs and the sale of berries, produce, and eggs. Luther had bought the old family homestead from his siblings for $1,000 around the end of WWI, but shortly before he died in 1972 he still owed the same amount he had borrowed fifty years prior—his daughter Ruth paid off the loan at that time.

During the Great Depression, Luther and Orpha’s hardships became so great that they had to send their oldest son Rodney away to live with a relative in Pennsylvania for several years. Grandpap wrote frequent letters to Rodney during this period in the 1930s. Fortunately, some of these letters have been preserved, for they offer a poignant glimpse into the lives of Luther, Orpha, and their children during those hard times. After finishing high school, Rodney and Bill (my father) both joined the government’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), as did millions of other young men then. Luther’s letters from home continued to them, and their meager pay checks were automatically sent home to Luther and Orpha by the government, keeping the family solvent during those crisis years. Whenever he could afford to, Luther would return a dollar or two of their pay to his sons in the CCC camps.

“I am sending you two dollars in this letter guess you can use it. I would send you more but I just had to finish paying my taxes. I got a letter from the bank the other week that they had to be paid May 1st. The government has sent men to all the banks to make a record of all the mortgages they hold, then they go to the courthouse and see if the taxes are paid…I got mine and John’s money for trimming trees and payed what I could May 1st then I payed the last one yesterday $10.00 out of your check, so I have them paid up to date, and one worry less. Mr. Alexander told me yesterday that he thought if Roosevelt got back another 4 years no body would own anything and he is a Democrat. I think it is getting pretty bad when they begin to nose into peoples private business. I hope that next month will see me through the worst of the year, and that I can keep the money you make for you….Hope you can get home soon. Also take good care of your-self….As Ever, Dad” (May 10, 1936)

In July of the year before, Luther had this to say:

“I want to take out the potatoes tomorrow hope we get enough to last us until the late ones come. I paid the interest money Sat. $36.00 and believe me I am just about broke. and the berries over, so I hope the beans are not so late coming on. It looks like it is all up to you and me to keep the wolf from the door, which I know is not fair to you, as you are at the age when you should be making it for your self alone, and saving some for future use. But let us hope things will get better, and that right soon. Well I must close as it is getting late, and I must get up early….”(July 29, 1935)

On occasion, Orpha wrote too. The following is from her letter to Rodney with news about a very sick baby (Donald) who nearly died. Luther and Orpha had already lost a baby years earlier.

“The baby is getting better slowly. Tuesday was four weeks since he has been in bed he can begin to set up a little now. I don’t know how long it can be until he can walk. You wouldn’t hardly know him he is so poor but he is beginning to eat good now. The doctor has been here 21 times and guess he will come a few more times.”

I’m sure they did not have health insurance then (who did?), but old-time country doctors charged people what they could afford to pay and often accepted barter. From the same letter there is news about the garden and crops, indicating how important this was to people who depended on the land for food and livelihood:

“Dad has old Pat here today plowing. he hasn’t the cantaloups planted yet. the piece is so weedy and hard to get in shape. The beetles and potato bugs are bad already. We have one patch that is up good and poles to them. The strawberries are starting to get ripe but they are not going to be very nice they are so knotty. The blackberries are nice they are white all over now with bloom…….Good Bye from Mother.”

The nature of their struggle and hard work is evident in many of Luther’s letters as well:

“I am still husking corn out at Uncle Walters we have one field done, but still have 15 acres yet to do, don’t know if we will get done before Christmas or not, just Walter and myself are husking he says he cannot afford to get any body else to help. We are going to butcher the 30th of this month, do you think you could get home for Thanksgiving and stay over till the 30th? I guess I will be short of help as John cannot be home either. Sometimes I have a notion to sell one of my hogs, so I can buy some pigs for another year, what do you think about it? I went hunting to-day, got 5 rabbits and a pheasant, I was by myself. I think rabbits are more plentiful this year, I seen quite a few I didn’t get…..As Ever Dad.” (November 15, 1937)

“We need rain very bad, the ground works so hard that you can hardly get it in shape to plant. I have the berries all plowed except the red ones. I planted about 500 last week and want to plant about them many more to-morrow. I planted about 500 hills of Beans yesterday for the first I have all the other plowing done….Guess Clifford told you that Grant Reeder shot hisself last week…” (May 10, 1936) [note: Grant Reeder was Amos’ father, my great-grandfather, who committed suicide in his barn just five miles away at Park Hall]

“Rodney what do you think of another Brother? You have another Brother born Tuesday 16th. Mother is getting along nicely and the baby is a cute little fellow….Mother said you should think of a name for it till you come home, also you should ask Aunt Myrtle if she would trade a girl for a boy….Also wish you a Happy Birthday sorry I don’t have any money to send you for your Birthday. But if we all live another year, I hope we can do better….With love, from Dad & Mother” (December 18th, 1930)

The winter of 1936 brought terribly cold weather, sickness, and of course more worries about money:

“It has been very cold here too, zero and below for the last couple weeks. I guess we have about 10 in. of snow and sleet to-gether. It surely is hard on the wood pile, I won’t have enough wood to last me through this month unless it gets warmer, and no way to get any from the mountain, guess I will have to cut some more apple trees. I have been keeping fires in the kitchen and room both all night to keep things from freezing….I haven’t made a cent this winter, only what little I get out of the eggs. I don’t know what I would have done if it wouldn’t be for what you are making. It seems to me things are getting worse than better….Mother put a dollar in one of your church envelopes for you….Hope you still don’t have to work out so much in this cold weather….take good care of yourself this cold weather and write soon….As Ever, Dad” (Feb. 2, 1936)

(Left to right in front) Ruth, Luther, Orpha, Doris

As if surviving the hardships of the Great Depression wasn’t enough tribulation for Luther and Orpha, they also had to endure sending off five of their sons to the Army during WWII and the Korean War (Rodney, Bill, James, Donald, and Paul). The official draft notice from the U.S. Army came for my father at Christmas time in 1942, and began with “Season’s Greetings: You are hereby ordered to report for duty…”. Imagine getting ordered to go to war with Season’s Greetings? Fortunately, all five sons came home, but it must have been agonizing at times, not knowing if they would. There is a wonderful photograph taken in 1955 showing Luther and Orpha posed proudly with those five sons—all wearing their military uniforms, and safely out of the service. The picture was taken in the yard of their home on a sunny summer day. I vaguely remember the event—odd impressions like how hot and itchy the wool uniforms were in the summer heat, and the smell of mothballs. They all must have been very proud and happy to be there.

(Front) Orpha and Luther

I don’t believe Luther or Orpha traveled very far from home—maybe 100 miles at most. What a difference from my life, where some years I probably traveled 20,000 miles at least. In my youth, after college, I may have unintentionally emulated some aspects of their homesteading lifestyle (albeit without 8 kids), when I lived for more than a decade in some very isolated places in the mountains of West Virginia and Virginia. I kept chickens and milk goats, planted big gardens, shot and ate deer, (also shot and killed my TV), cut and hauled my firewood, carried water from springs and old wells, froze my butt in drafty old outhouses, bartered for things like dental and legal services, knew and interacted with my neighbors, played the fiddle and banjo, and built my own house. I managed to get by on very little money—some years less than a thousand dollars.

In retrospect, it was a good time in my life and I was able to live that way because I learned self-reliant skills from my grandparents and parents. Eventually I had a career and little time for doing things for myself. But in retirement I returned to a lifestyle more in line with my roots and values. I spend more time outside with plants and animals instead of commuting or sitting in an office. I hope Luther, Orpha, Amos, and Margie would approve of that.

Author’s note: this article is excerpted from the preface of Those Who Came Before: Tracing Our Ancestors, by Dennis Slifer and Ann Herche Slifer, 2020, self published at blurb.com.

Thank You For Reading

Please Feel Free To Express Your Thoughts Below