My maternal great-great grandfather, Thomas Kennedy, came to the United States around age 25 which likely dates his immigration to 1846. Like many in this country, our ancestors came from Ireland during the Potato Famine. This famine began in 1845 and lasted until 1852.

According to his daughter, Margaret Jane Kennedy (my great grandmother), her father married five years later. Thomas’ own father had died when he was a young boy and he didn’t much remember him.

At some point (records do not say, but likely during or shortly after the famine) Thomas was able to bring two sisters to the United States. Then, he made an attempt to bring his mother and two younger brothers. On the way toward immigration which would have been by boat, of course, they stopped at a friend’s in Liverpool, England.

The wife of the host was away, and the husband prepared food, making biscuits. Apparently, he confused rat poison with baking powder, and my great-grandmother stated that (Thomas’ mother and two younger brothers, which would have been her grandmother and uncles) were accidentally poisoned and died there, in Liverpool. She states that the host and five children (presumably his) were also poisoned and “all but one died.”1

When reading accounts such as these, logical questions arise such as: who was the one person that did not die from the poisoning, and why?

Like many things, we may speculate and can never know.

Was it the host? Did he (for whatever reason) consume far less of the biscuits he made with the rat poison and thus be the only survivor? Or, was it another child? One might think a child would be far more likely to succumb to rat poisoning than an adult, but of course, children can be finicky eaters and perhaps one of the children was either older (in body weight) or very young (and took a bite and refused the rest?)

Many family stories exist in all of our genealogies and when I read this part, I vaguely recall my mother’s mention of this incident but it is very remote in my mind. Oral tradition is powerful, often accurate in major details, but of course, not precisely documented and open to questions. That I even have a vague recollection of being told the story of rat poisoning during my childhood–a story I couldn’t have even begun to make sense of, in whatever context it came up and was told me, at that age–shows that this certainly was a circulating and significant family story.

There is always some space of mystery and speculation that exists between words, and between the clearly known and the partially unknown.

__________

According to genealogy, Thomas’ second child (the first, Willie, died in infancy) Mary, was born in 1946. This would imply that he became a father pretty much during the same year as he came here (1846) unless that date is off. Also, it might imply he didn’t marry Sarah Williams until five years later and after he had children, but that is unclear. In another part, the writer of the extensive Carter (and associated families) genealogy book states they had tried (unsuccessfuly) to find a marriage certificate between the two (Thomas Kennedy and Sarah Williams).

I don’t know what this statement might imply (if anything) nor why it seemed significant enough to mention.

When I read the verbal account of Margaret Jane Kennedy (my great-grandmother) of her mother (Sarah Williams, my great-great grandmother, born in the United States, that somehow met and married Thomas Kennedy pretty much around the same time he stepped on to the sod of West Virginia from Ireland) I am struck by several things.

There seems to be a lot of spiritual contrasts that stand out to me between the family culture/religious/educational and other elements of legacy between the ancestors of my maternal grandmother (Mary Effie Carter Linger, daughter of Margaret Jane Kennedy Carter who was daughter of Thomas Kennedy…whom I will keep getting to in terms of observations of legacy and the spiritual element of generational cursing) and the culture/religious/educational and other elements of legacy that is known of John Curry Linger (my maternal grandfather).

The first thing I notice is that Margaret Jane’s account of her mother’s life and qualities included emphasis on her disposition, skills and Christian faith.

She states:

“She was a large woman, healthy, with wavy hair and blue eyes. She was always talking about something good and was happy to the end. She was an expert at weaving, spinning, quilting and knitting. She was a Methodist and a good Christian.”

I will return later to this statement of Sarah (Sally) Williams (Kennedy)’s

Christian faith later, since it seems to intersect in an odd way with that of my great-great grandfather, her husband, Thomas Kennedy.

The next thing I take note of is the description of Margaret Jane’s daughter, Emma Florence (whom she went to live with in California around 1910 after being widowed from her husband, Jacob Carter (who tragically died a premature death at age 42) in 1893. I wonder how Margaret Jane managed during those seventeen-ish-years, as a widow with six of their eight children under age eighteen, prior to her going to California with her grown daughter, Emma.

The description of Emma Florence Carter (Woods) is striking and couldn’t follow more closely the description of the virtuous woman found in Proverbs 31 if one wrote almost straight from the scripture texts. In fact, this leads me to believe and speculate that indeed, the spiritual legacy of Sarah (Sally) Williams was deeply ingrained in her daughter, Margaret Jane, and her daughter’s daughters (and I would have no reason to believe that only one of the five daughters followed in the taught/communicated spiritual legacy) which include not only Emma, but Emma’s younger sister Mary Effie (my maternal grandmother).

Emma Florence Carter (Woods) was the fourth child of Jacob Albert Carter and Margaret Kennedy (Carter). Born in 1879, she was 14 years old when her father tragically died at age 42. She is the daughter of Margaret Jane and Peter Elihu Woods. My grandmother, Mary Effie, was ten years old when her father, Jacob, suddenly died from a tragic (and somewhat odd) mishap.

The name Elihu sounded of biblical origin to me, and interestingly, I learned he was the young man who had been listening intently to the conversation between Job and his three miserable comforters, and toward the end of the book speaks up with criticism not only of Job but his three friends. More can be read in general account in Wikipedia, and I excerpt just one part:

“Elihu claims that the righteous have their share of prosperity in this life, no less than the wicked. He teaches that God is supreme, and that one must acknowledge and submit to that supremacy because of God’s wisdom. He draws instances of benignity from, for example, the constant wonders of creation and of the seasons.

Elihu’s speeches finish abruptly, and he disappears “without a trace”, at the end of Chapter 37.

But, back to the account of the life of Emma Florence Carter (Woods) and out of curiosity I intersperse parts of Proverbs 31:

Emma Florence Carter (Woods) was a matriarch, but an inspiration to her five children. She was a good cook and housekeeper, an organizer, and a strict disciplinarian. Her talents were many.

“At a very young age she learned to spin and weave, both wool and linen. She surprised doctors with her knowledge of medicine, which she had learned from gathering roots and leaves when drug stores were not common. She had an instinctive ability to cure many ailments without calling a doctor. She was artistic, and could do almost anything with here hands.

When she was twenty, she worked in a large department store in Pittsburg, Pa., as a milliner. At that time a milliner made silk and velvet roses to trim a hat, or tied ostrich feathers to make the large plumes that decorated women’s hats at that period. She could take combings of hair and weave switches for the elaborate hair arrangements.

Education was so important to her that regardless of financial problems, she managed to see that each of her children received a college education. Most people remember her great love of her family and relatives, as well as her friends. Regardless of how busy she was, she had a kindness that reached out to not only her own, but to children in the neighborhood. It was to Mrs. Woods that the children came with their skinned knees and little hurts. She could wipe a tear and bandage a sore with great gentleness.”

I find this account of this woman, Emma, who would be my mother’s aunt (my great aunt), quite a striking testimony of spiritual legacy. I’ve aimed (and seemingly failed in very human ways) at a number of things during my lifetime, and I would add this legacy of ancestral godly women (on both sides of my family) to those I would hope to have emulated in the past, and in whatever capacity I have yet to continue in pursuit during my remaining life.

I pause here because as part of my own journey of understanding not only my life story but that of my mother (which includes that of her mother, and her mother’s mother…) to say that in this past year of 2022, various events and factors led me on a bit of a personal quest to try to understand my grandmother, Mary Effie Carter (Linger).

I have more writings in progress, and this seems to be a good stopping/breaking/editing place from that which I start to write, in draft here, on January 2.

__________

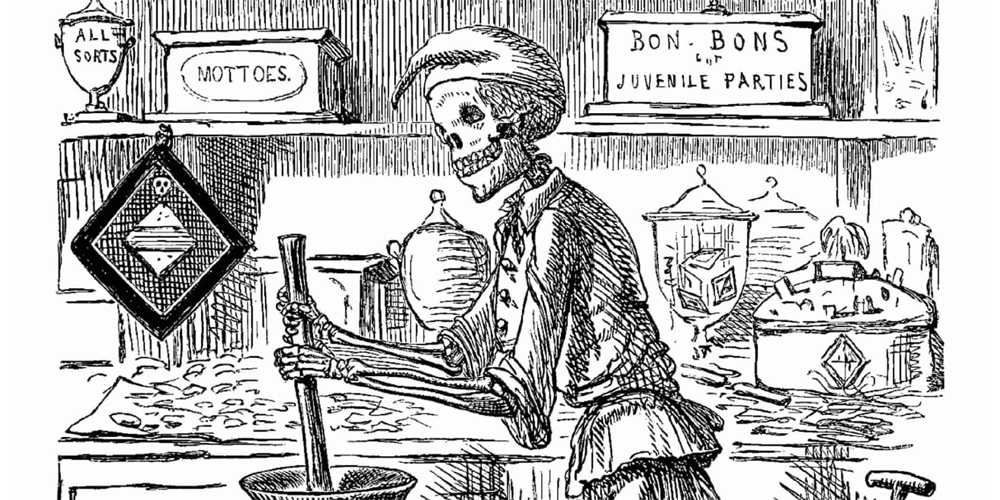

And, just as I was ready to share this piece and simply find some image of “rat poison” that might go with it, I learned something new through my search. First, I searched “rat poison” looking for a simple image…and realized modern boxed rat poisons would not do.

I then modified the search to “rat poison 1800’s” and was surprised to learn that arsenic is what was used. And, of course, that brought up a number of articles/images such as the ones I will tuck into the footnotes of this piece.2-3 (And I think the conversation in childhood with my mother over this family event was likely prompted by discussion of arsenic). And ironically, the first two articles were related to British history. It makes me partly wonder if the story was true, but it seems the contents of the family book were thoroughly vetted as best possible by the prominent California Judge Carter who assembled the massive collection.

It does say that arsenic was a white, powdery substance so I assume it is plausible that one might make such a mistake. Possibly. There just seems to be more questions to this abbreviated story by my great-grandmother, Margaret Jane, than any family will likely ever know!

__________

1The CARTER, ALKIRE, KENNEDY, WILLIAMS and Related Families, by Judge James M. Carter, published 1977, p. 190.

3Arsenic, Cyanide and Strychnine – the Golden Age of Victorian Poisoners

Thank You For Reading

Please Feel Free To Express Your Thoughts Below